- Heightened global uncertainty led by the unfolding tariff trade war simply means a weaker global outlook. Near-term Kiwi growth as a result has been downgraded. And weak productivity continues to hamper our long-run economic growth.

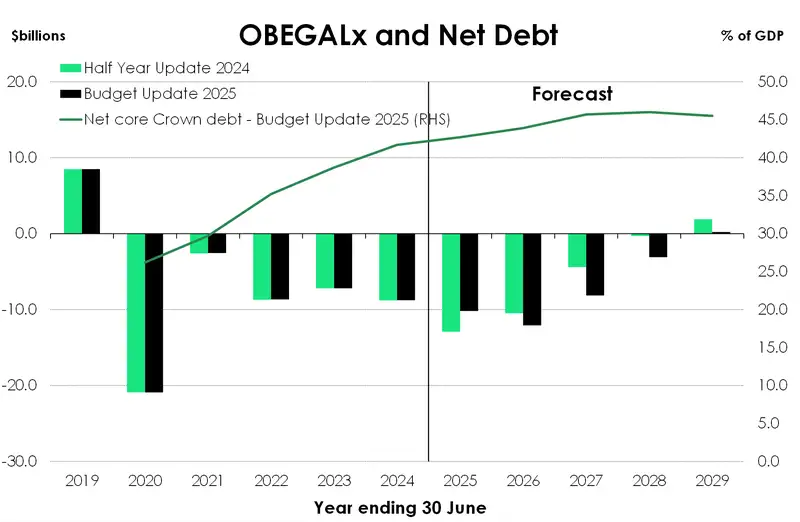

- A weaker economic outlook means a weaker fiscal outlook. No surprises. And that’s despite a reduction in operating allowances. Operating deficits are deeper in the near-term. A return to surplus is still achieved, but only just.

- The Government’s debt pile continues to grow in the near-term, hitting a peak of 46% but reached a year later. More debt means more issuance - $4bn more over the next four years to 2029.

As well-telegraphed ahead of the big day, Budget 2025 revealed an economic outlook hampered by global uncertainty, resulting in a weaker fiscal outlook with a focus on consolidation.

Heightened global uncertainty led by the unfolding tariff trade war simply means a weaker global outlook. Global growth forecasts have been cut left, right and centre. And being the heavily trade dependent country that we are, a downgrade to Kiwi growth, particularly in the near term, was inevitable. Despite the recent strength in the export sector, weaker export demand and reduced investment from tariff uncertainty are assumed to reduce New Zealand’s growth by 0.2% over the next two years. Growth later accelerates to 3% in 2027, but our persistently weak productivity constrains growth further out.

The operating surplus is still achieved, on paper, in 2029 – at the very end of the projections – but to an amount that needs a magnifying glass to see on a chart ($200mil or 0.0% of GDP). The weaker reality means more debt. The debt management office will have to issue an additional $4bn over the next four years to 2029. Net debt rises to a peak of 46% and remains above previous projections.

In terms of key policy initiatives, the new Investment Boost scheme is the cornerstone of Budget 2025 – the Growth Budget. The scheme involves a tax incentive to encourage investment in productive assets, like machines, tools, and equipment. Beginning from today, businesses can deduct 20% of a new asset’s value from that’s years taxable income, on top of normal depreciation. According to the Budget, Investment boost is expected to lift GDP by 1% and wages by 1.5% over the next 20 years – with half of these gains in the next five years. The policy is expected to cost the Government around $1.5bn per year.

The other headline-grabbing announcement centred around changes to KiwiSaver. Budget 2025 announced a staged increase in default employee and employer contributions to KiwiSaver. From 1 April 2026, the default rate will go to 3.5% and, from 1 April 2028, the rate will go to 4%. Other changes also include a reduction and means testing of the Government contribution, effective from 1 July 2025. The annual government contribution will be halved to 25cents for each dollar a member contributes, up to a maximum of $260.7. And members with an income of more than $180k will no longer receive it.

Tariffs weaken growth

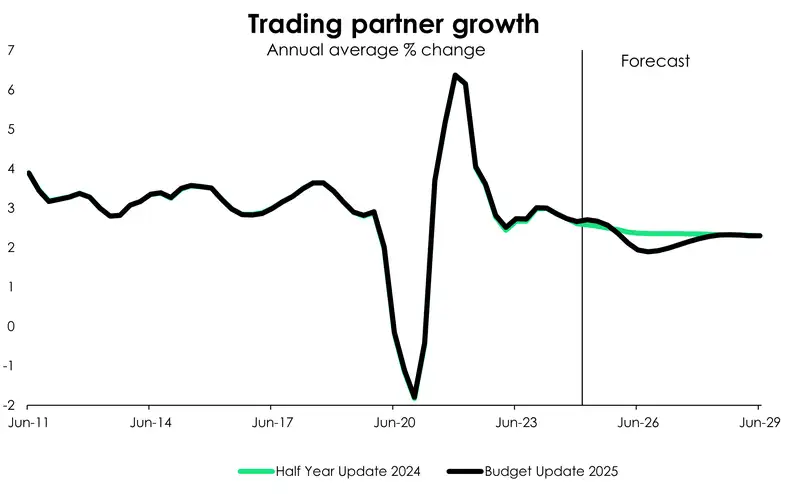

In her pre-budget speech, Nicola Willis told us to expect a downward revision to Treasury’s growth forecasts. Because increased trade tensions and heightened market volatility weaken global growth, and in turn, weaken Kiwi growth. Treasury’s latest forecasts assume growth across our major trading partners will average just 2% over the next two years, before averaging to 2.3% for the remainder of the forecast period. That’s well below the 3.3% average run rate of the past two decades.

Before we dig any further, it is important to note that Treasury’s forecasts were finalised on April 7th. That means, Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs were included in Treasury’s projections. But the subsequent 90 day pause on reciprocal tariffs to 10%, the current trade truce between the US and China, the single US-UK trade deal as well as specific item exemptions, have not been taken into account.

From our view, recent trade developments (post April 7) have taken us from a very bad situation, to something less bad, but far from good. The Kiwi economy will still experience lower growth than would have been the case prior to Liberation Day. A 1%pts haircut to trading partner growth under today’s conditions still seems fair. And as the Treasury states, “risks are skewed to weaker outcomes”.

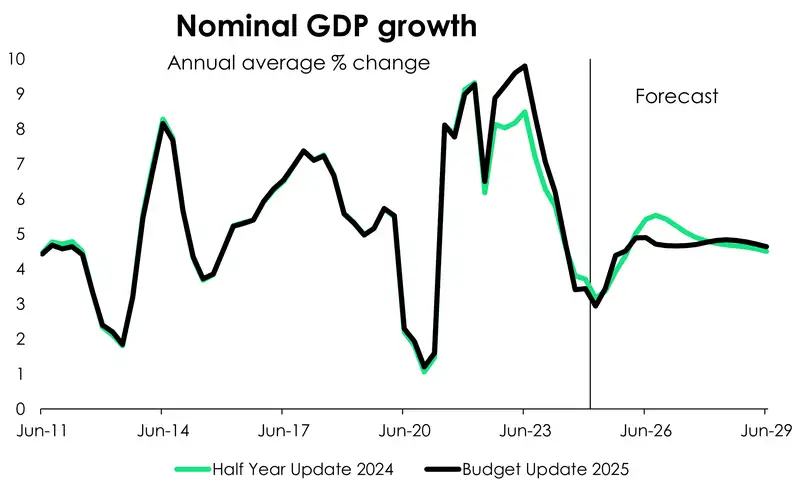

In any case, Treasury’s forecasts for growth are now lower in the near term before later accelerating and surpassing the Half Year Update forecasts. Despite the recent strength in the export sector, weaker export demand and reduced investment from elevated uncertainty are assumed to reduce New Zealand’s growth by 0.2% over the next two years. Annual average growth in the 2025 fiscal year is expected to contract 0.8% compared to growth of 0.5% laid out in the HYEFU. Similarly, growth in the 2026 fiscal year has been revised down to 2.9% from 3.3%. However, from 2027 onwards, growth is higher for the remainder of the forecast period compared to forecasts in December. Growth accelerates to 3% in 2027, in part supported by the newly announced Investment Boost policy. But growth slows from there to 2.6% by the end of the forecast period due to weaker productivity.

Nominal GDP growth is expected to slow to 3.5% in 2025 before accelerating to a peak of 4.9% in 2026. That’s a significantly lower peak compared to the 5.4% previously forecast, and is reflected in the weaker fiscal position.

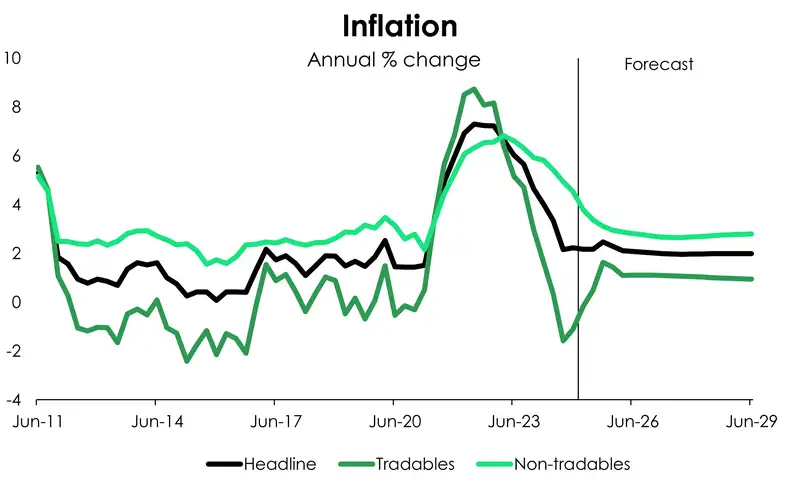

The other economic indicator on everyone’s mind right now is inflation. In recent times, other commentators have liked to focus on the higher price and inflation impacts of tariffs. Something we’ve pushed back on a lot. The big picture is that tariffs hurt growth. And a weaker global economy puts downwards pressure on prices in the medium term. Thankfully it seems, Treasury is on the same page as us, with little change in their inflation forecasts. Yes, in the near-term Treasury’s inflation forecast are a little higher with headline inflation expected to reach a peak of 2.5% in the September quarter of this year, compared to 2.1% at the Half Year Update. But the medium-term outlook remains at around 2%. Trading partner inflation is expected to be higher in the near-term, leading to a lift in tradable(imported) inflation. However the upward revision is balanced out by a faster than previously expected cooling in domestic inflation. Non-tradables (domestic) inflation is expected to fall below 3% by the Dec-25 quarter – a move not seen in Treasury’s previous forecast until the Jun-26 quarter. And it’s the non-tradables part of inflation that the RBNZ cares about the most. So, in Treasury’s perfect words “inflation is contained.”

Not an economic forecast… But because we’re on the topic of inflation, allocated in Budget 2025 was a portion of funding to develop and deliver inflation reporting on a monthly (rather than quarterly) basis. Hallelujah! Most of the developed world have had monthly inflation data for quite some time, and after many years of begging we’re excited to be moving into that space (albeit we have to wait two more years).It’s a great win, for us economists, and for all decision and policy makers too.

Several other key indicators were little unchanged. Treasury still expects unemployment to peak at 5.4% in the June quarter of this year, although takes a little longer to ease from here than previously expected. Similarly house price growth, remains virtually unchanged from Treasury’s forecast last December.

However, one forecast that does stick out is that of the 90-day bill rate. Compared to the HYEFU, the 90day rate ends the forecast period at 2.6% instead of 2.9%. Pointing to a 2.5% cash rate. Don’t get us wrong, we’re also calling for a 2.5% cash rate. But we’re calling for it this year, while the economy is still crawling out of recession. Treasury’s forecasts instead seem to indicate a lower cash rate at a time when the economy is returning to longer-term growth. Seem weird? Well, a lower cash rate will certainly make the models look better. And lower rates do mean lower interest on debt. So…food for thought, and we’ll leave it at that.

You’ll have to squint to see it

The Government’s books aren’t a pretty sight.

Core Crown tax revenue continues to grow over the five-year forecast horizon, but the track is $13.3bn lower compared to that presented at the Half Year Update. The discrepancy is largely owing to weaker economic conditions’ reducing the core Crown tax revenue $9.8bn. Tax policy changes as part of Budget 2025 also result in a reduction in tax revenue. The most significant of these is the Investment Boost scheme (a new tax deduction) as well as the changes made to KiwiSaver contribution rates.

On the other side of the ledger, core Crown expenses are on average $0.6bn per annum lower than forecast at the Half Year Update. The Government may have reduced its 2025 operating allowance to $1.3bn, but it’s more than offset by an increase in expense types such as benefits due to weaker economic conditions. The operating allowance for future budgets remains at $2.4bn.

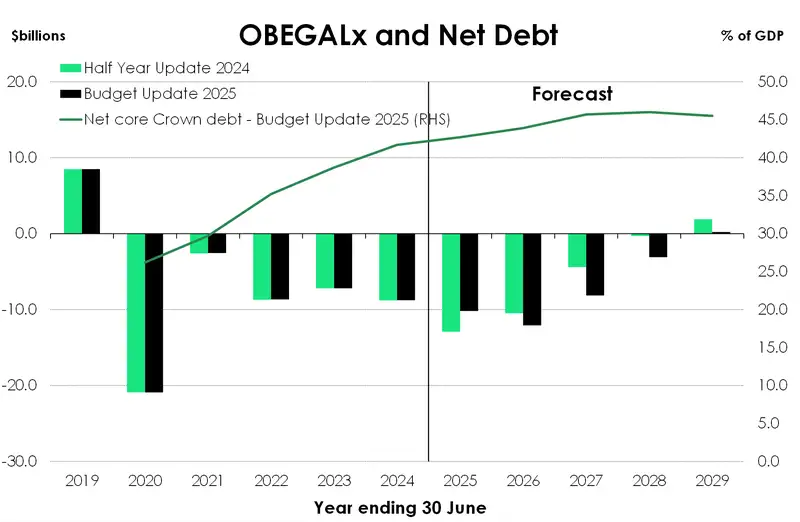

Piecing it altogether, the Government’s preferred measure OBEGALx is expected to be weaker across most of the forecast period, compared to the Half Year Update. The current year is the one exception, where the forecast deficit is around $2.7bn smaller than previously expected. The stronger result is largely due to lower costs to the Crown from unused pay equity settlements, as well as a marginal upgrade to core Crown tax revenue in the current year.

From the 2026 financial year, things get ugly. The Government’s operating balance is forecast to be around $2.5bn smaller on average per annum than previously expected. The deficit widens through the 2026 fiscal year to $12.1bn before gradually improving in 2027 as the economy bounces back and growth in taxable profits improves. As a share of GDP, core Crown tax revenue is forecast to rise from 27.4% in 2026 to 28.3% by 2029. At the same time, the Government’s expenses are projected to grow at a more modest pace. And as a share of GDP, is forecast to begin falling from 32.9% in 2026 to 30.9% at the end of the forecast period.

The Government’s books still return to black in 2029 (after 10 years in the red), but the surplus is significantly smaller – just $200mil (basically a rounding error), down from the $1.9bn pencilled in in the HYEFU. The amount is so small, it’s share of GDP is 0.0%.

With OBEGALx expected to remain in deficit over most of the forecast period, the operating cash position also remains in deficit. Overall, accumulated residual cash deficits are $5.3bn higher compared to the Half Year Update. Like the OBEGALx trend, however, the cash position is forecast to improve in the current year by $6.6bn. nonetheless, larger deficits are made in the outeryears – an average of $3bn larger per annum compared to the Half Year Update.

More debt issuance

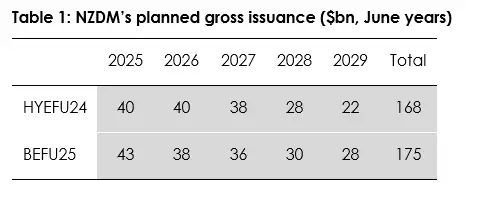

Deeper deficits, and net capital spending leads to cash shortfalls that are largely funded through additional borrowings. Forecast NZGB issuance in 2026 and 2027 has been reduced by $2bn per year. However, total issuance over the full four-year forecast period has been raised by $4bn, including a $6bn increase in 2029. The planned issuance profile is below:

As a result, net core Crown debt is forecast to increase. As a share of the economy, net debt is expected to peak at 46% slightly lower than previously forecast (46.5%). However, the peak is pushed out a year to 2028, and net debt is higher than previously expected at the end of the forecast period.

Capital allowances

Operating allowances are one thing, capital allowances are another. And consistent with the Government’s “Going for Growth” agenda, Budget 2025 announced a capital package totalling $4bn. The package comprises of $6.8bn of new spending, offset by capital savings of $1bn and the re-purposing of pay equity operating savings of $1.8bn from unused pay equity funding from 2025. Around $4.4bn of the capital package is forecast to be spent within the forecast period. The capital investments in Budget 2025 flow through to different parts of the Government’s balance sheet. However, the majority will be spent on physical assets. As announced in a pre-budget speech, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon, the boost to capital spending will be split across primarily health, education and defence.

Fiscal impulse

Treasury’s fiscal impulse analysis provides a measure of how much fiscal policy is either adding to or taking away from aggregate demand from one year to the next. Over the forecast period, fiscal settings are assessed to be contractionary, but slightly less than in previous updates. Overall, Treasury’s fiscal analysis averages -0.5% over the entire forecast period, compared to the 0.6% average in both the HYEFU24 and BEFU24 updates. At the same time, the yearly profile has changed. For 2024/2025, the fiscal settings are slightly less expansionary than predicted at the HYEFU. Meanwhile in 2026, the fiscal impulse has gone from a contractionary -2.6% to a now expansionary 0.18%. Thereafter however, fiscal settings remain contractionary for the remainder of the forecast period with deeper contractions in the 2027 and 2029 fiscal years than previously forecast at the HYEFU. Again, the changes here are not huge, but given inflation has returned back within the RBNZ’s 1-3% target band and the economy is still crawling its way out of recession, a weaker near-term fiscal impulse helps raise the case for the RBNZ to do more in the here and now.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.