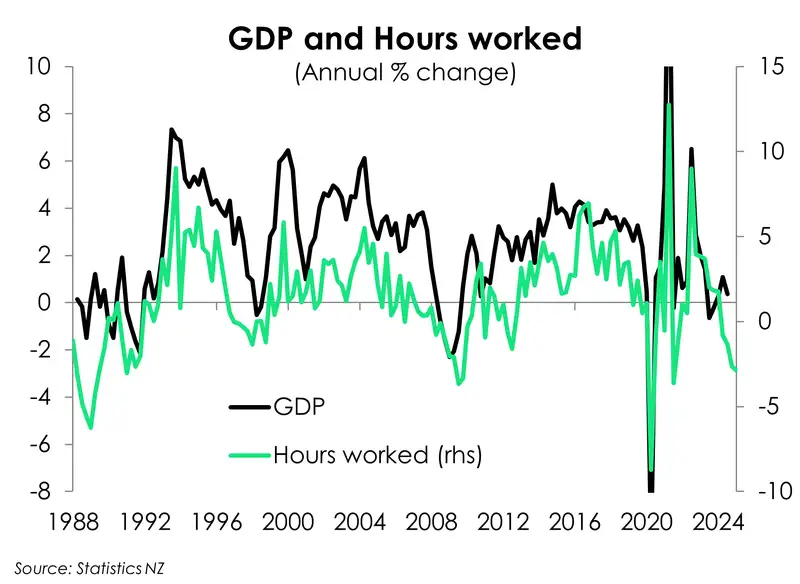

- The Kiwi unemployment rate was unchanged at 5.1%, but firm appetite for labour is still clearly lacking. Employment barely grew, hours worked is down 2.9%, and wage growth continues to moderate.

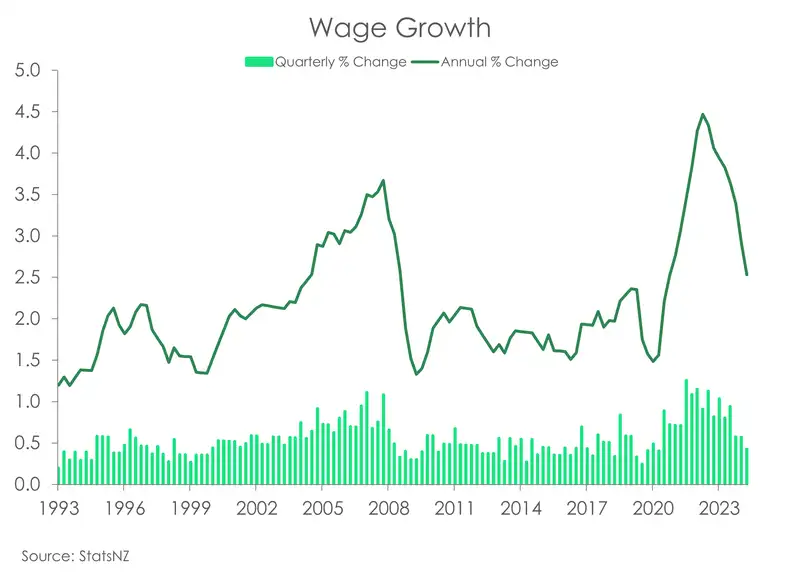

- Wage pressures continue to cool. The private LCI, a measure of pure wage inflation, has slowed to 2.5%, moving further away from the 4.5% peak two years ago. Weaker wage inflation points to weaker core inflation.

- Today’s data reinforces the need for further monetary policy easing. Downside risks to medium-term inflation are growing given the soft labour market and dimming global outlook. We expect the RBNZ to cut the cash rate to 2.5% by year-end.

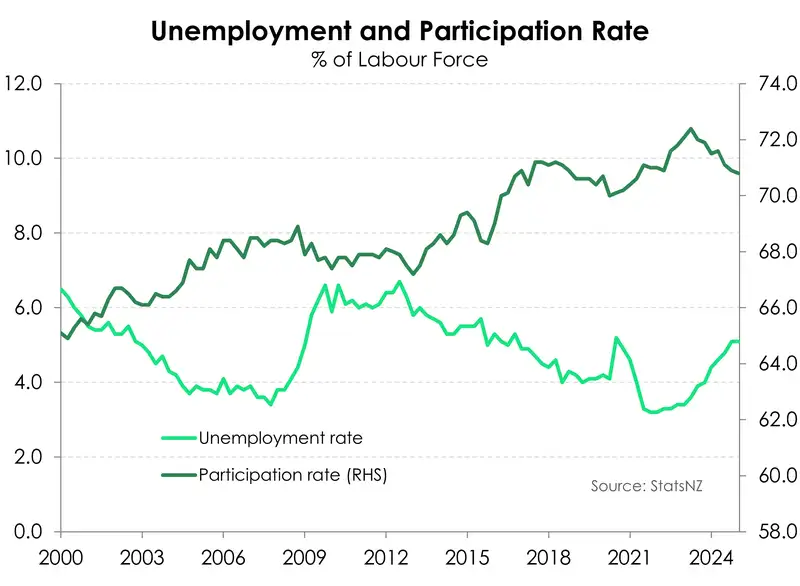

Today’s employment report looked to be a little better than expected, but it wasn’t. The unemployment rate came in at 5.1%, below the RBNZ’s estimate of 5.2% and our forecast 5.3%. But that was it. That was the “good news”. The details of the report were weak, as expected. Workers may not be losing their jobs, but many are losing valuable hours. The underutilisation rate rose, even as unemployment remained steady. The number of people with jobs, but not enough hours, rose again. The trend was also highlighted in the fall in full time employment, and rise in part time. What matters more for the economic outlook, is the hours worked. Hours worked fell a hefty 2.9% over the year, and has been declining for 5 consecutive quarters. Declining hours is also being met with easing wage pressures. More and more workers are receiving smaller and smaller pay rises. For example, the number of workers receiving a pay rise above 2% but below 3% has been steadily increasing for 7 quarters. And the wage bill (private sector Labour Cost Index) rose 2.5% over the year, down from 2.9%yoy last quarter and a peak of 4.5%. That’s indicative of a sharp recession. And so too is the drop in participation. The participation rate fell, again, to 70.8% from 70.9%. That’s down from a peak of 72.4% (in June 2023). That’s a mighty fall. Put simply, the labour market is not as attractive as it once was. The demand for workers has fallen, and would-be-workers give up and leave.

Everything in this report shows the scars of the recession. Even the ‘unchanged’ 5.1% unemployment rate may look better than expected compared to last quarter, but it has risen from a low of 3.2% in 2022.

Today’s report supports the call for lower interest rates. Demand for labour has clearly softened. Wage inflation is cooling quick. And we should have stimulatory monetary policy (not the current restrictive setting). We expect another 100bps of rate cuts to lower the cash rate to 2.5% year end,

Lack of love for labour

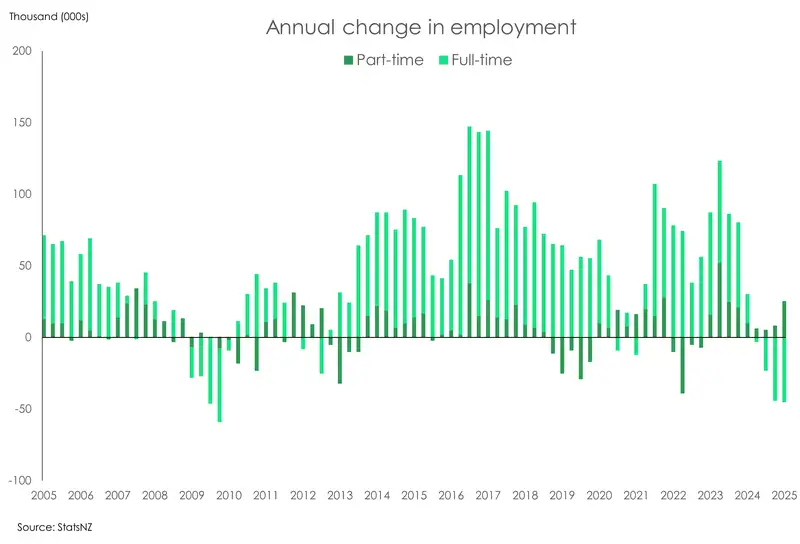

Sprinkled throughout the March quarter set of labour market numbers were clear signs of a lack of appetite for labour. Employment barely grew, total hours worked is down close to 3%, the full-time workforce is shrinking, and wage growth continues to moderate. The underutilisation rate – a better measure of slack in the market – lifted from 12.1% to 12.3%. In the last year, the number of underutilised increased by 35k, primarily led by an increase in unemployment. However, the last 12 months have also seen an almost 17k increase across those underemployed (part time workers who want to and are available to work more hours) and available potential jobseekers.

Employment growth managed to eke out a 0.1% gain over the March quarter. But it follows two straight quarters of decline. The low base is underscored by the weak annual rate, with March employment 0.7% below last year’s levels. And the lay of land is changing, with a shift in the quality of work. The number of people in full-time employment fell by 45k in the last year, with the workforce shrinking 1.9%. Meanwhile, the part-time workforce added 25k, expanding 2.2% over the year. However, there is a clear desire for more work. Compared to a year ago, there has been a 12% increase in the number of full-time and part-time workers wanting to work more hours than they usually did. According to Stats NZ, “this is driven mainly by people who said there was not enough work available”. Needless to say, the cutback in full-time employment was a key influence in the decline in total hours worked,

The total number of hours worked have been in decline since March last year. With hours worked falling for the last five quarters, the annual print is far from pretty. Outside of the 2020/21 covid period, the number of hours worked recorded the deepest annual decline since 2009. Compared to a year ago, total hours worked fell 2.9%, down from 2.6% last quarter and getting close to the 3.3% slide in 2009. Fewer hours is another warning sign of weak economic activity for the March quarter.

Bargaining power back with employers

Growing slack in the labour market and a slowdown in inflation has shifted the balance of power back to employers. The shift is shown by the continued cooling in wage costs. The costly combo of high inflation and labour shortages lit a fire under wage growth, with the private labour cost index (LCI) hitting a series-high of 4.5%. Two years later, that fire has been put out, with the LCI falling to 2.5% - the lowest since September 2021. The distribution of annual wage growth also underscored cooling wage pressures. The proportion of jobs that received a pay rise was little different to last quarter at 59% (albeit significantly smaller than the 66% share last year). However, the distribution of wage increases continues to move away from the chunky increases of more than 5% which was once the favoured rate. That proportion rose to a high of 40% in 2023, and has fallen to just 17%. Majority are pocketing increases of between 3% and 5%. And now that that inflation has corrected lower, the proportion receiving wage increases of more than 2% but less than 3% has been steadily increasing, from 6% in March 2023 to 11% in March 2024. It’s yet another clear sign of softening employment demand.

The Quarterly Employment Survey (QES) provided further evidence of cooling wage pressures. Private sector average hourly earnings lifted just 0.3% over the quarter (from 1.3%) and eased from 4% to 3.8%. Given easing domestic price pressures amidst a weak economic backdrop, there’s reason to expect further slowdown in wage growth.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.