Mortgage rates have risen a lot over the last two years. From the depths of the Covid response, a record low cash rate of just 0.25% (with talk of negative rates) meant mortgage rates were slashed to 2-to-3%. Our first chart plots the mortgage rate curves, with the record low in mid-2021.

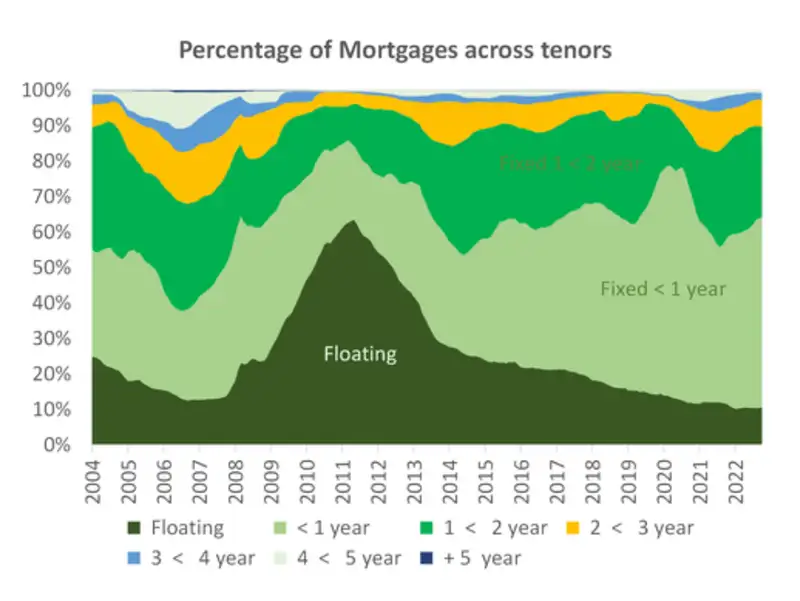

There was an aggressive 1- and 2-year fixed rate campaign in 2021. Mortgage holders took these rates, and enjoyed a record reduction in interest deduction. Some even took the 3-to-5 year rates, nearer 3%. But they were outliers, representing less than 10% of mortgages outstanding. People with 5-year rates are less than 1%. Indeed, 90% of people fix for less than 2-years (or sit on floating rates).

The last of the record low mortgage rates are rolling off. Our second chart shows the split of mortgage rates across tenors. About 10% of the book is on floating, with around half on fixed rates for 1-year and under, and a quarter fixed for 2-years. The important point here is that it takes up to 2 years for previous interest rate hikes to fully feed through the system. The 525bps of RBNZ tightening, taking the cash rate from 0.25% to 5.5%, is still feeding through for some.

The rapid rise in the cash rate, coupled with a sharp uplift in global interest rates, has seen all interest rates rise. Mortgage rates jolted from the record low 2’s to now mid 7’s and even 8’s. And the effective mortgage rate - the average rate paid across the stock of all mortgage lending - is 5.4%, up from the record low of 2.9% in 2021. With more mortgages yet to roll off, the Reserve Bank expects the effective mortgage rate to lift to 6.4% by mid-2024. The average share of disposable income going to interest payments is also estimated to double from it’s 9% low in 2021, to around 18% by mid-2024. On mortgaged households, it is expected to lift from less than 10% to over 20% by year end, and continue higher into 2024.

It's the end of cheap money

So far, signs of acute financial stress have been low. The number of arrears have increased over the past year, but they’re rising off historic lows. Current, and forecast, arrears remain well below GFC levels. As pointed out in the Reserve bank’s November Financial Stability Report, the economy has proven resilient to high interest rates, thanks to strong labour market and wage growth.

But pockets of stress will emerge. Buyers made decisions on the rate they were given at the time. They made decisions on rates in the mid 2’s to 3’s and were tested on rates only up to 6%. They’re now rolling off onto rates of 7% and higher. And new loans are being tested at 9% and higher.

A lot hinges on the labour market. Low unemployment has supported households. But in a high interest rate environment, demand weakens, businesses pull back, and unemployment rises. We’re seeing that already.

Unemployment has risen from its record low of 3.2% to 3.9%. That climb will continue. We expect unemployment to reach a peak of 5.5% late next year. The RBNZ’s estimate is a little stronger with a peak of 5.3%. Any increase in unemployment produces a sore spot but a peak at around these levels will achieve a soft landing. The material risk is if things turn uglier than forecast. Unemployment rates beyond 7% are when we start to see a more exponential rise in mortgage defaults…

“More borrowers are likely to fall into arrears over the coming year, given there can be long lags between an increase in debt servicing costs and borrowers falling behind on their obligations. In addition, if unemployment continues to increase and domestic economic activity continues to slow, some indebted households will have fewer options to avoid missing their debt repayments.” (RBNZ Financial Stability Report, Nov’23)

The result of ‘higher for longer’ monetary policy is simple. Indebted households will pay a much greater proportion of their disposable incomes on interest. Household budgets have already been stretched by the cost-of-living crisis. Households are spending a lot more, to get a lot less. The rapid rise in the cost of essential items has forced households to spend less on more discretionary items. We’ve seen this in our credit and debit card data over the last year or so. The pullback in home contents and furnishings is a classic example. The average number of purchases is sitting ~5% below pre-covid levels. And the restraint to splurge began a year ago. Non-essential goods and services remain under pressure.

Households with debt are paying a lot more on interest repayments. And the main asset, to which the debt is tied, has fallen close to 20% in value. That’s a knock to confidence. We continue to forecast a mild contraction in economic activity, largely due to the stresses on household spending.

In order for money to be lent, money must be saved. We speak at length about the borrower, but often ignore the saver. On the flip side, savers are earning more. We’re no longer hearing from the saver. As interest rates were slashed to the record lows of 2021, savers were crying foul. Term deposit rates dropped below 1% over late 2020-2021. Many savers, especially retirees reliant on nest egg interest, came under pressure. Now, term deposit rates are the highest they have been since the 2008 GFC. The chart below plots the 6-month term deposit rate alongside the wholesale 6-month bank bill rate. Savers can now receive 6% (or higher) on term deposits. Term deposit rates, for the first time in a long time, now exceed inflation (currently 5.6%, and headed lower into next year).

For the love of charts

We have a lot of household debt. And with larger debt burdens comes a greater sensitivity to interest rates. Debt-to-income has been relatively stable over the last decade, but is much higher than the levels of the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s. A 7% interest rate today is a lot more impactful than a 7% rate 20 years ago.

Most mortgage lending goes to owner-occupiers. The main development in mortgage lending has been the lift in first home buyers (FHBs). Whereas investors, under fire from the regulator and previous Government, have retreated. The introduction of a longer brightline test, the removal of interest deductibility, changes to consumer credit access (CCCFA), and general market conditions have weighed on investor appetite. We may see a rebound in investor activity if the incoming Government reverses, or at least partially reverses, these constraints.

Interest-only lending has declined as a proportion of total lending. The growth in mortgage lending has been on P&I (principal & interest) terms. It’s safer, and households are injecting equity.

The mortgage rates offered in 2021 were the lowest ever recorded. People made investment decisions on these rates, nonetheless, and pain is being inflicted by the rapid rise in interest rates over 2022 and 2023.

It’s not all about housing. Banks lend to businesses as well. And the chart below highlights the higher risk and default rates in general business lending. Lending in agriculture has seen the greater share of defaults over the last 15 years. Default rates are expected to rise the most, as costs climb (including interest costs) and commodity prices remain soft.

We have witnessed the most aggressive hiking cycle in the RBNZ’s history. All in response to the return of the inflation beast. While inflation remains high above the RBNZ’s 2% target midpoint, the distance is narrowing. Inflation is moving in the right direction. We are winning the war. But for the RBNZ to uphold its inflation-fighting credentials, interest rates will have to remain high and restrictive for some time yet. However, 15-year-high rates should be enough to see inflation back at the target 2%. No further tightening from the RBNZ is needed. Phase II will be a normalising in monetary policy. And we may see the rate cutting cycle commence next year.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.