- The Government opened its book for all of us to see. And it wasn’t a pretty sight. A delayed economic recovery has led to the Govt running deeper deficits and a delay in the return to surplus.

- The Kiwi economy lost momentum in the middle of this year. The recovery has begun, and is set to gather pace next year. 2026 should see a strong cyclical rebound in growth. But then structural issues see that growth taper in the long-term.

- A weaker economic outlook means a weaker fiscal outlook. No surprises. Operating deficits are deeper in the near-term. And that’s despite relatively steady growth in expenses. Consequently, the return to surplus has been shifted out a year to 2030.

- The Government’s debt pile continues to grow in the near-term, hitting a peak of 46.9%. More debt means more issuance.

2025 was a year that disappointed. For households, businesses, forecasters (us included), and now the Government. The recovery we were meant to have didn’t eventuate as hoped nor expected. It’s no new story. And as such, is by no surprise that the Governments fiscal books showed little improvement in today’s Half Year Update.

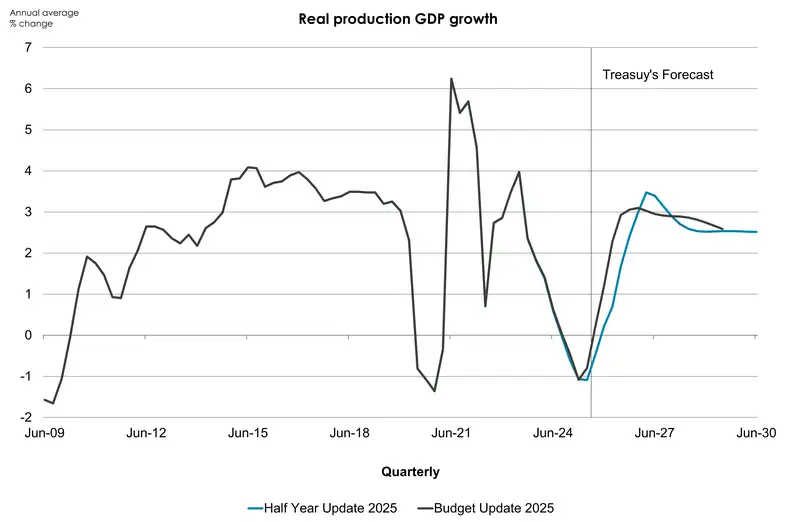

The growth outlook from Treasury is overall weaker compared to their update in May. The loss of economic momentum over the second half of this year has pushed out the recovery into next year. However, underpinned by monetary policy stimulus and higher terms of trade, Treasury now expect a stronger rebound in growth over 2026. We agree and are just as eagerly ready for a robust recovery. Yet moving away from the cyclical recovery it seems we may start to encounter some more structural issues. Treasury’s forecasts for the outer years of the forecast horizon remain lower than their earlier projections at Budget as slower population growth and softer labour participation are set to weigh on potential growth. Both factors undoubtedly caused by the recent downturn. But both factors which may take some time to come right.

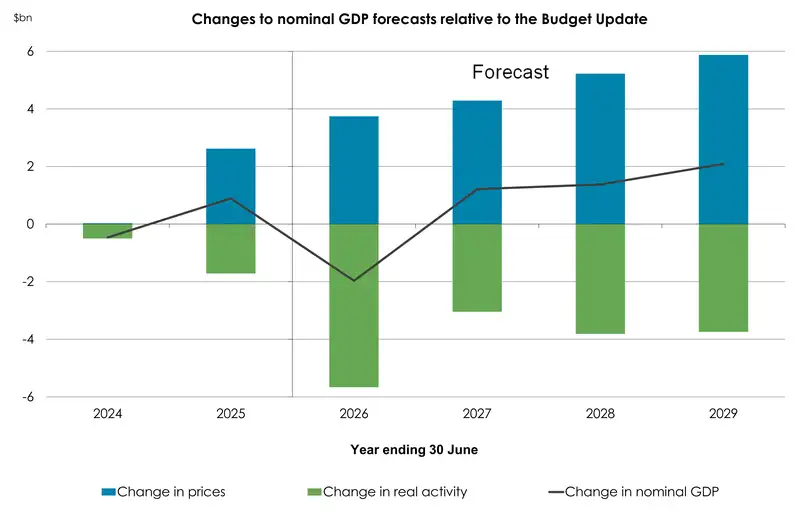

One saving grace for the Government is that the nominal economy, the part that matters for the revenue base, is not as weak as it could have been. Higher inflation (still within the RBNZ’s 1–3% target band) offsets some of the drag from slower real growth. While the nominal economy is smaller than Budget forecasts in 2025/26, it moves higher thereafter, providing some relief to fiscal accounts. But not a lot…

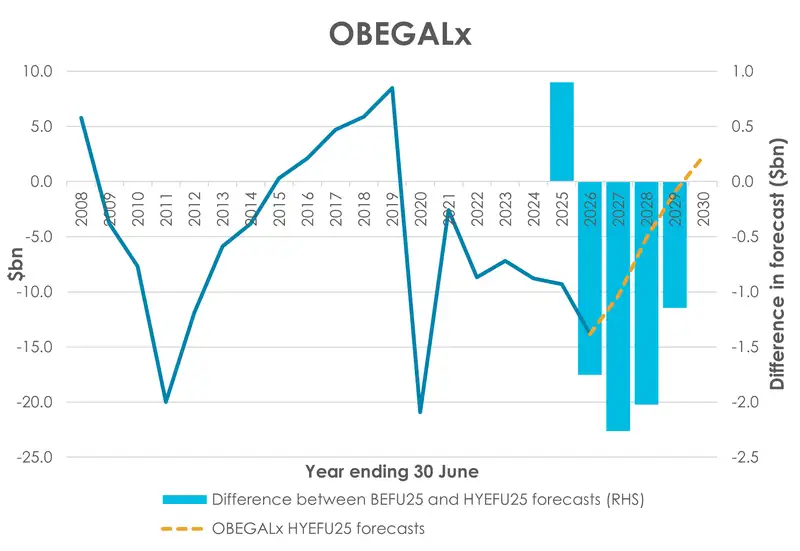

A disappointing economic recovery means a disappointing fiscal recovery. Today’s update revealed a deterioration in the Govt’s books. The Government is expected to run deeper deficits than anticipated a few months ago. In the current year, the operating deficit is forecast to be almost $2bn wider than last forecast in May. The downgrade reflects a slower economy, lower tax take, but steady expenses. The return to surplus has been pushed out a year. Saved by an additional year to the forecast horizon, the Govt’s books do go back to black within the next five years. By 2030, OBEGALx is forecast to record a surplus of $2.3bn or 0.4% of GDP.

A weaker operating position means a larger cash shortfall for the Govt. And that means a greater debt pile. Net debt is forecast to hit a new peak of 46.9% of GDP.

As for the Govt’s policy priorities for Budget 2026, Finance Minister Nicola Willis told analysts and media in the lock up today to expect:

- The Government continuing to run a tight ship

- The operating allowance remaining at $2.4bn

- Health, education, defence, and law and order will be the priorities

- And as in Budgets 2024 and 2025, savings and reprioritisation will be crucial

That’s all we got. A teaser of what’s to come. Just like the movies, the Minister has left all the plot twists and big bang announcements for Budget 2026.

Structural issues weigh on potential growth

Tweaks here and tweaks there. Much has changed since Treasury’s last forecast update in May.

On one hand, the global outlook has improved significantly compared to the Budget update when Treasury’s forecasts were locked in just two days after Liberation Day. Since then, we’ve seen a major roll back on tariffs from the US administration. Trading partner growth has not been as heavily hit as feared. And the Kiwi export sector has largely cruised through the shockwaves of tariff changes to come out as our top performer for 2025. However, on the other hand, the domestic economy hit a wall in the middle of this year. Kiwi business investment slowed under the paralysing fear of Trumps tariffs. And interest rates were yet to be at levels supportive of the recovery we needed. Together those two factors saw a sharp decline in activity over the June quarter and virtually no growth over the first half of 2025.

Against this backdrop, Treasury now expects a delayed and weaker recovery through the 2026 fiscal year followed by a stronger rebound in 2027 relative to their previous forecasts back in May. However ultimately growth is still lower across the forecast horizon.

The softer 2026 outlook reflects the loss of momentum in the June quarter, a deeper cyclical low, and greater spare capacity in the economy. Kiwi growth is forecast to average just 1.7% in the 2026 fiscal year. By 2027, however, growth is expected to average 3.4%, marking a period of above-trend growth underpinned by monetary policy stimulus and higher presumed terms of trade. But alas, all good things come to an end. Beyond 2027, Kiwi growth is projected to slow to around 2.5% for the remainder of the forecast period. Overall leaving Kiwi growth below levels forecasted back in May due to weaker population growth weighing on our potential growth.

How this all flows through to the size of the nominal economy is quite interesting. Because while real GDP is set to be weaker than forecast in the budget update, nominal GDP growth is set to be slightly stronger. It’s an outcome that reflects higher inflation experienced and forecasted since Treasury’s May update.

Nominal GDP is forecast to be smaller by $2bn in the 2026 fiscal year relative to budget forecasts with higher prices providing little offset to the slower recovery of the real economy. However, from 2027 onwards the impact of higher prices dominates the impact of lower real activity. By June 2029, the nominal economy is expected to be $4.6bn larger than previously forecast. And adding 2030 to the forecast horizon, nominal GDP is projected to reach $551bn.

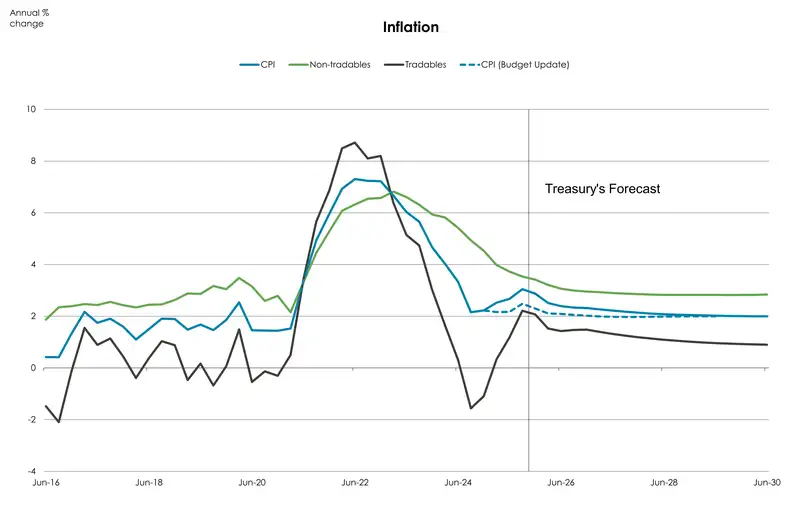

It’s worth noting that Treasury’s changes to the inflation outlook aren’t dramatic in terms of the overall price trajectory. Their May forecasts simply proved too optimistic. Back then, Treasury expected inflation to peak at just 2.5% in the September quarter. Instead, we saw inflation accelerate to 3%. But like us, Treasury expects the current 3% headline rate to mark the peak in this recent bout of inflation. And Treasury see inflation trending back toward the 2% midpoint into next year though a touch slower than our own forecasts. We still see risks that inflation undershoots 2% around this time next year. Treasury instead see annual headline inflation at 2.3% around that time.

Looking at other forecasts, Treasury’s forecasts for unemployment may seem a little more pessimistic with the unemployment rate forecast to lift further from 5.3% to 5.5%. However, Treasury does note that these forecasts were finalised prior to the release of the Q3 jobs report which saw signs of stabilisation across the labour market. We think 5.3% should mark the peak in this cycle.

A last thing to note is that Treasury’s forecasts for the 90-day rate implies a 2% cash rate. Although Treasury again have acknowledged that this forecast was finalised in October prior to the November MPS and the recent improvement in economic data. Treasury’s comments acknowledge that the likelihood of a further cut to the cash rate is lower.

Deeper deficits

The Govt’s books ended the 2025 fiscal year in a healthier state than forecast in May. The strength in the starting point, however, doesn’t look like it’ll persist. The current fiscal year is running behind earlier forecasts. Because the economic recovery has disappointed. Not only has the Govt’s fiscal position deteriorated since Treasury’s May analysis, but it’s now expected to be a slower fiscal recovery from here. Ultimately, the return of the Govt’s books to surplus has been pushed out a year to 2030 – the end of the forecast period. That comes as no surprise given that the May estimates had a surplus of just $200mil. It was basically a rounding error to begin with, easily forecast away. Net core Crown debt has also been revised higher.

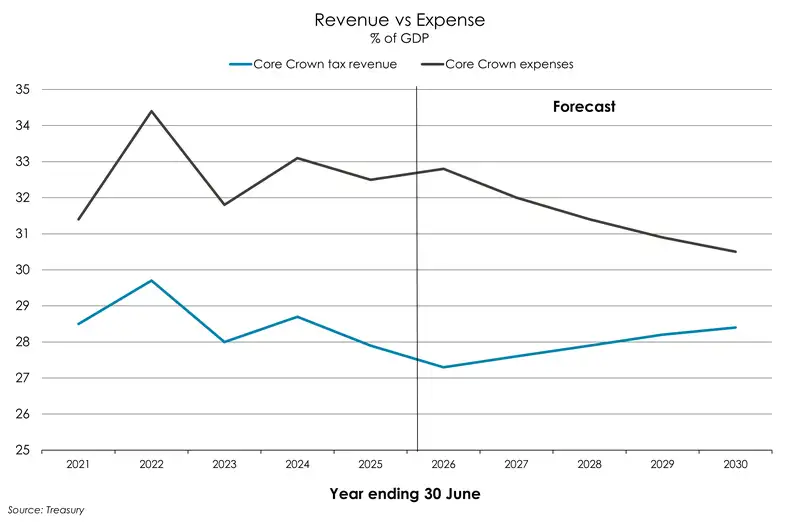

Core Crown tax revenues continue to grow over the five year forecast horizon, but the track has been lowered in the near-term. Compared to the Budget Update, $0.8 bn has been stripped out of the tax take in both 2026 and 2027. The downgrade largely reflects weaker real economic activity and a softer labour market. But the growth in nominal GDP contributes to an increase in core Crown tax revenue through the forecast period. The lift in revenue comes from higher wages, consumption and business profits. By 2029, revenue forecasts are $200mil higher than compared to the Budget update.

On the other side of the ledger, core Crown expenses are expected to initially rise by $7.4bn to be 32.8% of GDP in 2026. But 32.8% of GDP should mark the peak. From 2027, expenses are forecast to fall as a share of GDP to 30.5% by 2030. The Govt has maintained operating allowances for new net expenditure to $2.4bn per Budget. Sticking to script means that the rate of expenditure growth is slower than nominal GDP growth.

Putting less revenue and more expense together means a delayed return to surplus. The Govt’s preferred measure of the operating balance, OBEGALx, has been running at a deficit of around 2% over the last few years. And in the current year, the deficit is expected to widen to $13.9bn or 3% of GDP – almost $2bn worse than forecast in May. However, If we adjust for the impact of the economic cycle, Treasury estimates the deficit to be smaller. By their calculations, around one third of the deficit is due to the economic downturn. The rest is structural in nature.

From 2027 onwards, the operating deficit narrows. Saved by the addition of another year, the Govt’s books do still return to surplus within the forecast period. The $200mil surplus that was initially expected to be achieved in 2029, has been rubbed out and replaced by a $900mil deficit. But the following year, 2030, shows a return to surplus to the tune of $2.3bn or 0.4% of GDP. That’s less of a rounding error this time. The recovery is underpinned by steady growth in tax revenue as the economy grows and more modest growth in expenses due to smaller Budget operating allowances.

Fiscal impulse

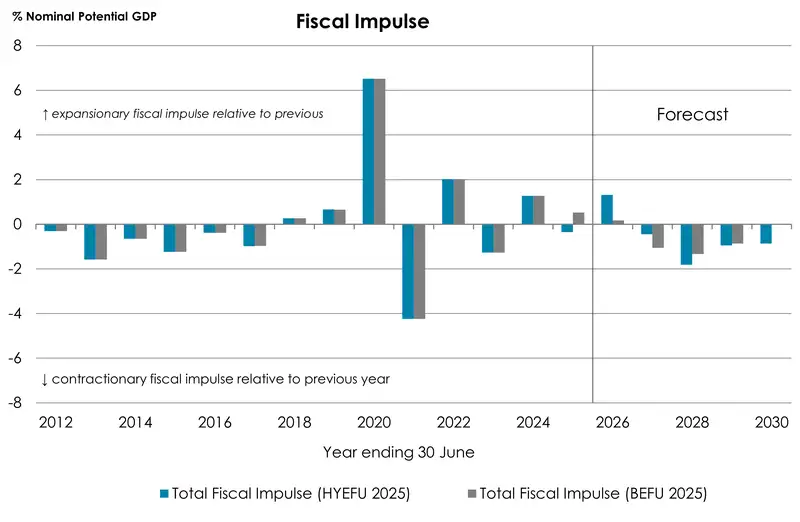

Treasury’s fiscal impulse analysis provides a measure of how much fiscal policy is either adding to or taking away from aggregate demand from one year to the next. Over the forecast period, fiscal settings are assessed to be more contractionary than previously thought. Overall, Treasury’s fiscal analysis averages -0.6% over the entire forecast period, compared to the -0.5% average in the Budget update. But the yearly profile has changed. Fiscal settings in 2025 were reassessed as contractionary at -0.35% compared to the Budget Update forecast of a slightly positive 0.52%. That means 2026 is forecast to be expansionary at 1.32% relative to the previous year. Thereafter, the fiscal impulse weakens. It’s a point in favour of keeping the monetary policy at stimulatory settings to strengthen demand and grow the economy.

A bit of rebalancing in bonds

Deeper deficits mean larger cash shortfalls. The residual cash deficit is expected to grow from $6bn in 2025 to $14.8bn in the current year before peaking at $23.3bn in 2027. And majority of the accumulated residual cash deficit reflects spending on capital investments. The cash shortfall is largely being funded through additional borrowings.

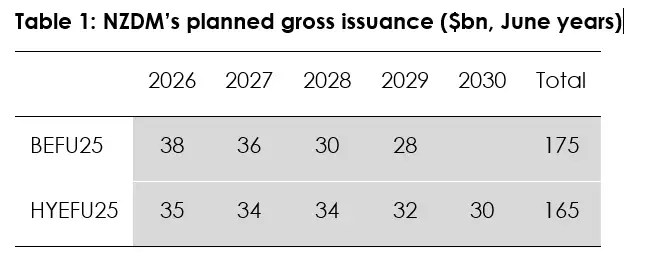

Forecast NZGB issuance in 2026 and 2027 has been reduced by a total of $5bn. And there will only be three syndications in the 2026 fiscal year rather than the four indicated at the Budget Update. And extra $8bn of bonds has been added in 2028 and 2029. It’s a bit of rebalancing after the NZDM revised the minimum liquidity buffer to $10mil from $15mil. The liquidity buffer is a portfolio of cash and high-quality liquid financial assets. The buffer is there to be used during periods of market dislocation, when financial costs may be elevated or markets are hard to access. Overall, $3bn has been added to the borrowing programme over the forecast period.

Table 1: NZDM’s planned gross issuance ($bn, June years)

As a result, net core Crown debt is forecast to increase. As a share of the economy, net debt is now expected to peak at 46.9%, slightly higher than previously forecast (46.0%).

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.